Well into adulthood, Henry Dorough and his wife Paula Burke always ate ham on Easter Sunday.

But now that they raise sheep, a leg of lamb or roasted shoulder is the holiday fare at HD Farm in Talladega County, which Dorough started nearly two decades ago.

They’ve joined a tradition that is thousands of years old—serving lamb for Easter or Passover celebrations. Rich in religious symbolism, lamb is fundamental to the most sacred observances in both Judaism and Christianity, including the Passover Seder.

“I used to do a Seder meal for our church during Lent,” says Dorough, who also is a county agricultural extension agent. “I’d cook a leg of lamb or shoulder roast on an outdoor grill with a little hickory smoke. Then I’d slice it and put it out for the Seder ceremony.”

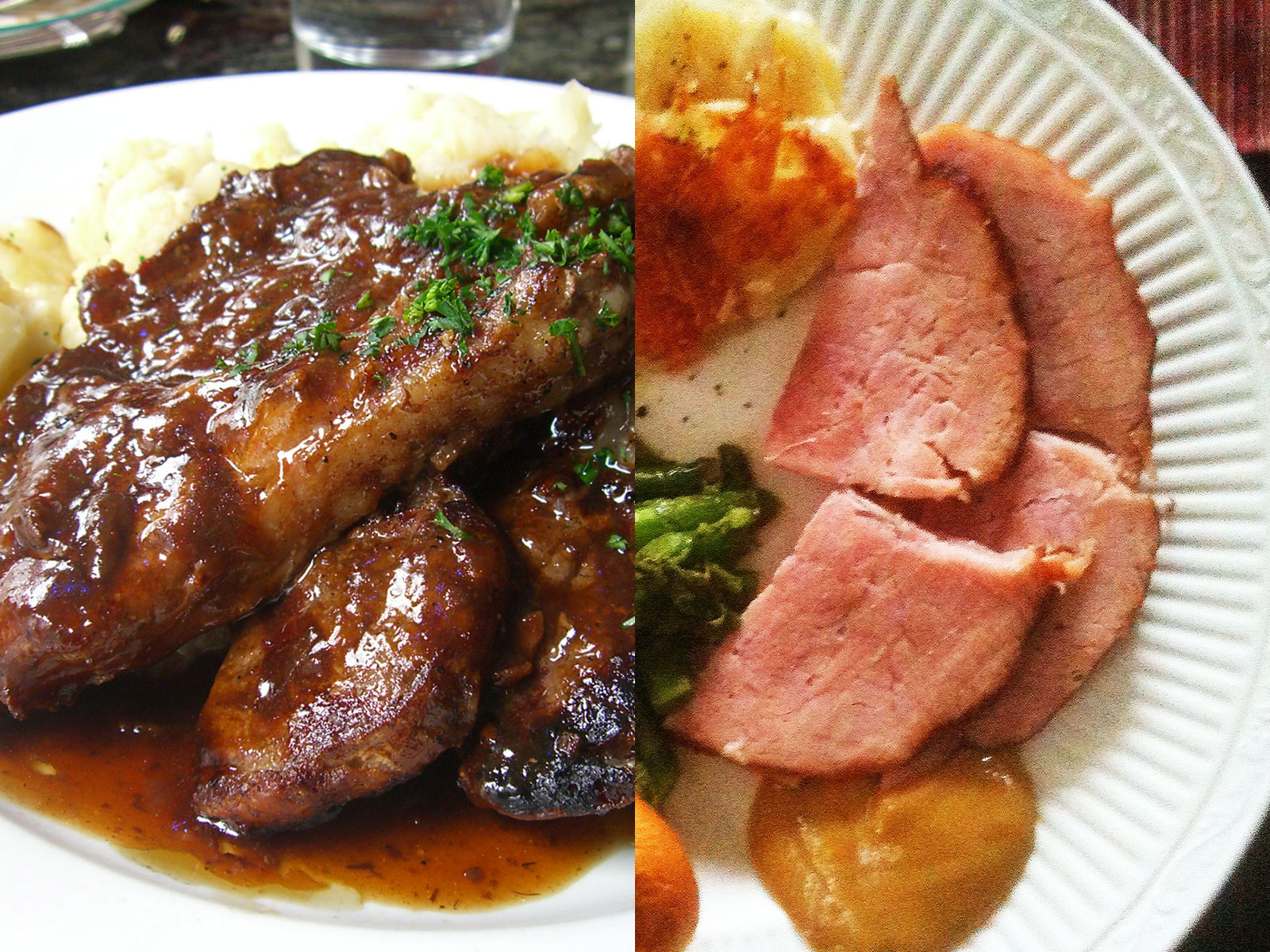

Lamb Dinner at HD Farm (Contributed)

Lamb was standard at Easter in the United States until the mid-20th century, when the development of synthetic fabrics slashed the need for sheep and their wool. As the prices of lamb meat and pork started to invert, ham became The Meat for feeding a holiday crowd.

This month, leg of lamb is $8.99 per pound in Birmingham; whole spiral-sliced ham is $2.49 a pound. Prices for pastured-raised lamb and pork are higher.

In the south, ham is so traditional it’s hard to imagine Easter without one on the table. Before refrigeration, farm hogs were butchered in the late fall when the weather was cool enough to safely process, preserve and cook the meat. Sufficiently cured and aged by the start of spring, smoked hams were the tastiest thing in many larders when Easter rolled around.

Lamb is associated with spring as well; most sheep raised for meat are born then. HD Farm takes a different approach, timing its breeding to promote fall births so its pasture-raised lambs would be ready just before Easter.

Spring is the inspiration behind a budding Easter tradition for Zack Redes, the former chef de cuisine at Highlands Bar and Grill, and his girlfriend, Katica “Kate” Stojanova. It stems from her Macedonian roots.

The couple gathers people they hold dear for a meal of lamb and veligdenska salata, a Macedonian salad with the spring garlic that starts popping out of the ground around Easter. It also includes eggs, radish, feta cheese, scallions, fresh parsley, and olive oil.

“That’s part of the traditional table at Easter,” says Stojanova, who lived in the Balkan country until she moved to the U.S. before college. “For holidays we’d put on these big feasts with friends and family around the table.”

Previous years, Redes has prepared lamb shoulder—slow-roasted for seven hours—and rack of lamb. This year the menu includes lamb cooked over a wood fire.

“It’s very rustic,” Redes says. “I’m excited to eat this freshly roasted whole lamb and this Easter salad.”

Lamb leg, which feeds 6-8 people, is the most common Easter cut. Bone-in is more flavorful than boneless. Trimming exterior fat is optional.

Roasting lamb leg is simple. Skip the marinade or wet brine and start by simply rubbing down the meat with salt, minced garlic, and herbs like rosemary, cumin, or marjoram. Place it under the broiler to brown the outside and then roast it in a medium oven, 350 degrees.

Medium-rare meat (130 degrees -135 degrees on a meat thermometer) takes about 20 minutes per pound; for medium-well (150 degrees), cook it roughly 28 minutes per pound.

Pull the leg from the oven before it reaches the desired internal temperature; it will gain a few degrees more while resting. There are two main hunks of meat on either side of the bone, so carve one, flip and take care of the other.

Dorough, the lamb farmer, recommends skipping mint jelly as a condiment.

“It’s kind of like a steak,” he says. “If you order a ribeye and they smother it in sauce, it wasn’t good to start with. With lamb, if you have a good product to start with, you’ve put the right seasonings on it, and cooked it well it shouldn’t need anything when it’s done.”