I spent much of my childhood hung up on where I lived, or rather, trying to explain to others exactly where I resided. My house was situated in an undefined gray area between tiny Alabama towns. The roads that I lived on didn’t have formal names; they were known by their postal route codes, all designated “Rural Routes” followed by a number. There was not an option for cable television because companies didn’t run cables out that far from town. For years, my parents had to drive me miles to where a school bus would pick me up because public buses also did not come out to where we lived.

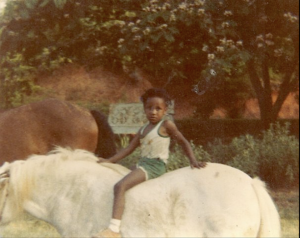

Dobbins on her family farm in Hale County (Alabama Humanities Alliance/Contributed)

Country living was rife with these inconveniences. I grew up thinking about home as an isolated, liminal space. I wasn’t going to run into anyone I knew because our house was its own castle, nestled between grand oaks and pines. Home was the equivalent of falling from the map, disappearing off the radar, like some strange science fiction thriller. It was Bermuda Triangle geography.

But my seclusion taught me the beauty of taking my time and listening to the world around me, and it distinctly shapes how I approach filmmaking and writing today. I spent my formative years taking in the beauty of birdsong, communing with nature, and being alone with my own thoughts. Alabama made me a patient person, and that translates to my work as an artist. I am an advocate of slow and thoughtful storytelling. I delight in meandering trajectories and narrative threads.

As an adult, my curiosity has taken me all over the world. For decades of my life, I thought that my going out in the world was going away from Alabama. But years ago, as I was taking in the towering, otherworldly orange dunes of southern Africa’s Namib Desert, I realized that I am always seeking rural spaces akin to home.

Family in Pickup by Roslyn Jones, Dobbins’ cousin (Alabama Humanities Alliance/Contributed)

At the time, I was on a nature walk with a Namibian guide. You might think there wasn’t much to see in the desert, a place I always assumed was barren by definition. However, scratch that sandy surface and you find all sorts of elusive wildlife. Beetles emerge from the dunes at dusk and dawn and stand on their front legs in a sort of handstand, letting the moisture from the fog collect on their bodies and trickle down into their mouths. Water is scarce, so this is how they survive. I told my guide about my family farm in Alabama and my grandfather’s intimate knowledge of southern fauna and flora. I told him about catfish farming and Black farmers making a way in spite of decades of oppressive government tactics. Instantly, we started speaking a common language, one of people who were raised on the land.

“We are not so different,” he says. “You know what it is like to not have everything within reach. That is country

living, but we make a way.”

“Yes,” I said. “We always do.”

For years, I thought my upbringing was a disadvantage — a descriptor I needed to work beyond. As a writer and filmmaker, I often attempted to overcompensate for my rural origins. In my youthful naivete, I believed that rural Alabama was void of true artistic refinement because that’s what the world taught me.

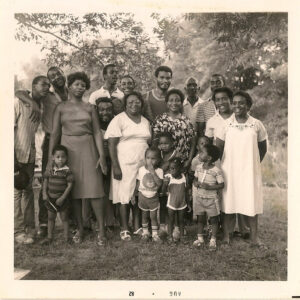

Jones Family Reunion, 1982 (Alabama Humanities Alliance/Contributed)

As a kid, I watched everything: westerns like Rawhide and Gunsmoke; science fiction like Star Trek and The Twilight Zone; and various comedies and dramas. Television was escapism, in a sense, but I was always confronted with distortions of the rural and Southern. Even then, I understood that the people writing and playing me on television were not from the rural South. But I could see myself as they saw me, and it was rarely a flattering portrayal. Seemingly harmless television shows like The Beverly Hillbillies reinforced this idea that rural folks only had streaks of ingenuity or inspiration by mistake, and even then, the end result was often tragic. We could only be brilliant by accident because our isolated upbringings meant we were backwards and limited by definition.

My artistic journey has demanded that I shake the shame of growing up in the backwoods. I am not the first artist to reckon with my connections to home in my work. For many artists, it takes a lifetime to come to resolution with the places that molded us. I will admit to years of struggling to uncover my own love for the rural South. Many of my formative experiences were tainted by slights directly linked to the color of my skin. I cannot write about the rural without writing about how it almost smothered me to death. It’s a difficult thing to be an artist in spaces that thrive on conformity, familiarity, and insularity.

It was only after extensive travel through Africa, Europe, and the United States that I could return to the South with new eyes. Leaving home freed me up so that I could truly see home. Immersing myself in the work of rural artists and writers further enlightened me. I will never forget how I felt the first time I saw William Christenberry’s photography. His work took the wind out of me because I could immediately see that he was one of us. He captured country spaces with care. Not only did he cast the rural with an insider’s gaze, but he immortalized spaces that were mere minutes from my house. It was Christenberry who helped me see that I didn’t grow up “nowhere” as I had always imagined. Rather, I grew up in a place rich with beauty and tradition, and people were eager to see my world. Writers like Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston filled in what was missing from my school’s required reading list — stories that reflected the rural experience from Black women’s perspectives. There are traces of them all in everything that I do.

…

In a brief titled “Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau,” the Census Bureau notes that it “defines rural as what is not urban — that is, after defining individual urban areas, rural is what is left.” Defining vastly different cultures, people, and topographies by “what is left” seems like a disservice, but I understand the quandary. In fumbling through attempts to explain what rural is, I often note all the city services and cultural amenities that we do not have, or I speak about all of the wild natural spaces that we do have. My rural world is one of paradoxes. At times utopian with its wild fauna and flora — the sweet breezes of spring, rife with promising notes of honeysuckle — this world is simultaneously dystopian for marginalized people.

(Alabama Humanities Alliance/Contributed)

Rural means so many different things to so many different people, and it means different things to me at different times. My definition constantly evolves based on my perspective and, often, my location. Now, as an adult, I can say that my work is deeply rooted in the rural South. I make photographs and films, and I write stories and articles. Everything I create is motivated by truth, honesty, seeing, and listening. In many ways, Alabama made me a good observer. And once I stopped trying to shake its soil from my shoes, I became a better storyteller, too.

The art, books, and films that I consumed in my formative years distorted my initial vision of the rural American South. The world often grapples with the rural through these channels. These mediums influence how we are seen and treated in the world. For these reasons, it is critical that we advocate for and support artists who are native to the communities that they are documenting. Investing in local artists and writers is the way to counter false and harmful narratives.

My life and career are testaments to the influential nature of the humanities. I am writing this article from my apartment in Reykjavik, Iceland, a sort of second home and another place that puts Alabama in perspective for me. Ironically, this will be the place where I finish my documentary film Alabamaland. Being here in Iceland has helped me better define my relationship with rural Alabama. Outside of the city, Iceland is one of the most rural places I have ever lived. It feels like home but is away. Here, I feel safe grappling with rural American art.

Being an artist is all about making connections, often between seemingly disparate places, people, and themes. It is a sort of gathering, and it’s this connective work that makes me who I am.

April Dobbins is a photographer, writer, and filmmaker from Hale County. Her documentary film project, Alabamaland, is an ongoing exploration of Black family farms.

This story is reprinted from the 2023 issue of Mosaic magazine, published by the Alabama Humanities Alliance. Read the issue in full at alabamahumanities.org/mosaic.