Before the chants, before the speeches, before history was written into law, the Civil Rights Movement was sung.

Music moved through churches, jail cells, and city streets, carrying grief, faith, anger, and hope when words alone fell short. These songs did more than accompany marches; they helped people endure them. They were an offering of courage in moments of fear and unity in the face of violence. In Alabama, where some of the movement’s most defining moments unfolded, music became both a response and a form of resistance. Protest songs honored lives lost, named injustice directly and reminded those fighting for equality that they were not alone. Let’s take a look at some of the songs that helped shape the movement, tracing their histories, their connections to Alabama, and the role they played in turning collective struggle into a shared voice.

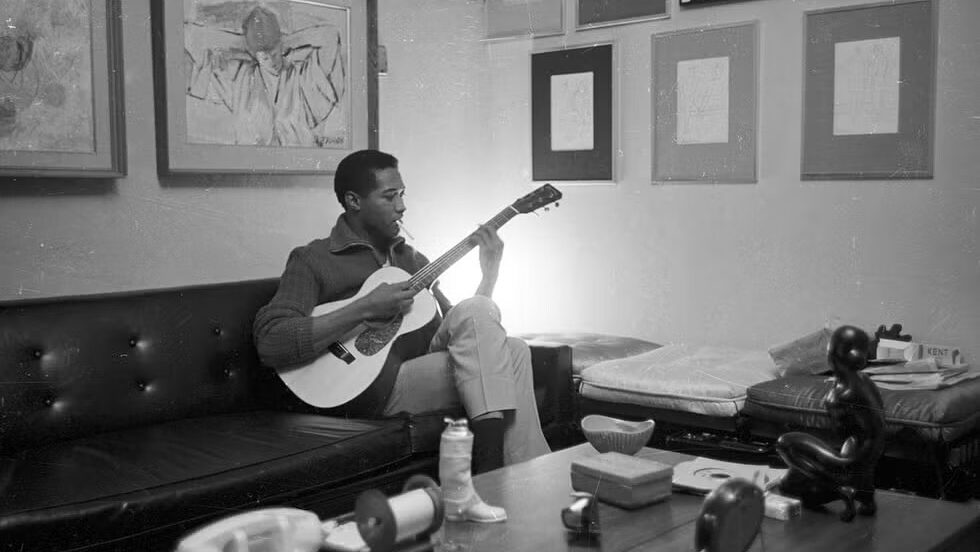

(John Coltrane/Facebook)

Alabama

Composed in 1963, “Alabama” was John Coltrane’s response to the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which killed four Black girls–Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley. The instrumental piece draws from the rhythms of Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy for the girls translating speech into sound to express collective grief and restraint at a moment when words felt insufficient. “Alabama” became a powerful form of protest, though it contains no lyrics, it confronts the tragedy head on, ensuring that the devastation in Birmingham will never be forgotten.

Birmingham Sunday

Written in 1964 by Richard Fariña and performed by Joan Baez, “Birmingham Sunday” responds to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing through a quiet, storytelling approach. The lyrics unfold slowly, emphasizing the normalcy of the morning before the weight of the loss becomes clear, allowing listeners to sit with the human impact rather than the violence itself. It named Birmingham directly, and by doing so it carried Alabama’s grief beyond the state, making this horrific event more than a local tragedy, it is a shared national mourning. In doing so, “Birmingham Sunday” became a form of musical witness, ensuring the moment was not only grieved for but remembered.

(Document Records/Facebook)

We Shall Overcome

Before it became the anthem of the movement, “We Shall Overcome” was a hymn. Its roots trace back to “I’ll Overcome Someday,” written by Reverend Charles Albert Tindley, a Methodist minister and the son of formerly enslaved parents, who believed deeply in faith as a source of endurance and hope. Decades later, Zilphia Horton, Guy Carawan, and Pete Seeger reshaped the song and transformed it from a spiritual into a shared language of protest. As it moved through the Civil Rights movement–notably during the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965– its slow tempo and simple lyrics made it easy for the crowds to sing it together, reminding activists that they were part of something larger than themselves. “We Shall Overcome” became a collective promise for progress.

I Shall Not Be Moved

“I Shall Not Be Moved” began as a spiritual grounded in faith and personal conviction, its central image–standing firm like a tree–resonating deeply with those facing hardship. As the Civil Rights Movement unfolded, the song became a way for individuals to voice resolve, especially in moments when standing still required as much courage as marching forward. In Alabama, the song was embraced not as a rallying cry, but as a quiet assertion of dignity by those who refused to be intimidated or displaced. Ella Fitzgerald’s 1967 recording helped preserve that spirit, carrying the song beyond the movement itself and framing resistance not as spectacle, but as an unwavering choice to remain rooted.

A Change is Gonna Come

Sam Cooke began writing “A Change is Gonna Come” out of personal frustration, grief, and exhaustion after the repeated accounts of racism he experienced while traveling and performing in the segregated South, including being turned away from a hotel while on the road. He used this song as a way to confront the limits being placed on him despite his success. Recorded in 1964 with a sweeping, symphonic arrangement by René Hall, the song marked a clear departure from Cooke’s earlier pop sound, showing a real and vulnerable side of the artist. The ballad was released just weeks after Cooke’s death later that year, the song carried an added weight, becoming an anthem of quiet endurance during the Jim Crow era and resonated deeply with Black communities across the South. Considered one of the greatest compositions in American music history, “A Change is Gonna Come” captured the emotional cost of justice, and the determination to believe in it anyway.

(High Museum of Art/Facebook)

Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama

Recorded during the height of the Selma voting rights movement, Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama captures the music of the Civil Rights Movement in a raw and real way. The tracks are not polished studio recordings or performances by well-known artists, but songs sung by ordinary people–activists, church members, and marchers–who relied on music for strength and connection. Familiar freedom songs such as “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” “This Little Light of Mine,” and “Which Side Are You On?” appear not as performances, but as collective voices rising together. Rooted in spirituals and call-and-response traditions, the recordings reveal the humanness of the movement itself: unguarded, imperfect, and deeply felt. In listening, you don’t just hear history, it places you within it. It is easy to visualize people holding one another steady, singing through fear, fatigue, and faith, and reminding themselves that they were not alone.

The Legacy of Protest Music

Together, these songs trace the Civil Rights Movement not as a single movement, but as a collection of voices–some famous, many unnamed–responding to injustice in real time. In Alabama, where grief and resistance so often intersected, music became a way to endure, to remember, and to imagine something better than even when the path forward was uncertain. From polished recordings to raw field songs, these sounds remind us that the movement was not carried not only by speeches and marches, but by people steadying one another through song. During Black History Month, listening to these voices is not just an act of remembrance, it is a reminder of the humanity at the heart of the fight for justice.

Want more stories like this? Join our newsletter for more stories rooted in Alabama, delivered to your inbox every Friday.