When driving through Birmingham, there is one ever-present landmark that creates a stark silhouette against the city’s skyline. The subject of speculation, rumors, and numerous ghost stories, Sloss Furnaces is one of Birmingham’s most seemingly sinister features. While locals differ in their degrees of knowledge around the local landmark, Sloss Furnaces has a deeply interesting history that is undeniable in its importance in shaping the Steel City. The following is the true history of Sloss Furnaces as told by the team supporting the landmark.

In the years following the Civil War, railroad men, land developers and speculators moved into Jones Valley to take advantage of the area’s rich mineral resources. All the ingredients needed to make iron lay within a thirty-mile radius. Seams of iron ore stretched for 25 miles through Red Mountain, the southeastern boundary of Jones Valley. To the north and west were abundant deposits of coal, while limestone, dolomite, and clay underlay the valley itself. In 1871 southern entrepreneurs founded a new city called Birmingham and began the systematic exploitation of its minerals.

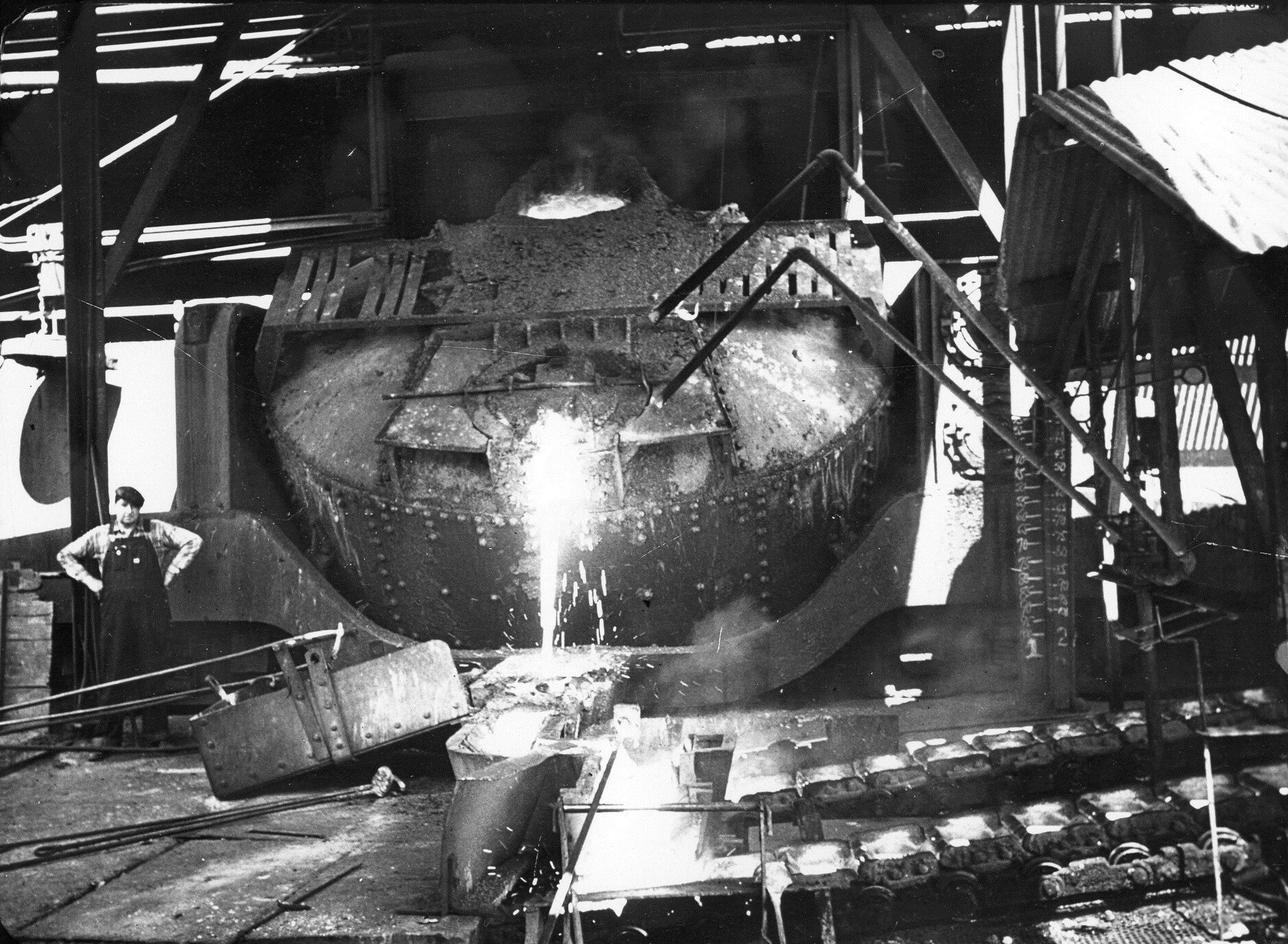

(Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark/Facebook)

One of these men was Colonel James Withers Sloss, a north Alabama merchant and railroad man. Colonel Sloss played an important role in the founding of the city by convincing the L&N Railroad to capitalize completion of the South and North rail line through Jones Valley, the site of the new town. In 1880, having helped form the Pratt Coke and Coal Company, which mined and sold Birmingham’s first high-grade coking coal, he founded the Sloss Furnace Company, and two years later “blew-in” the second blast furnace in Birmingham.

Construction of Sloss’s new furnace (City Furnaces) began in June 1881, when ground was broken on a fifty-acre site that had been donated by the Elyton Land Company. Harry Hargreaves, a European-born engineer, was in charge of construction. Hargreaves had been a pupil of Thomas Whitwell, a British inventor who designed the stoves that would supply the hot-air blast for the new furnaces. Sixty feet high and eighteen feet in diameter, Sloss’s new Whitwell stoves were the first of their type ever built in Birmingham and were comparable to similar equipment used in the North.

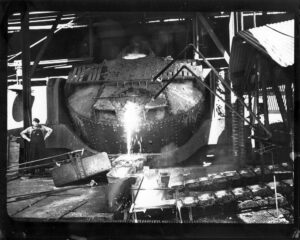

(Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark/Facebook)

Local observers were proud that much of the machinery used by Sloss’s new furnaces would be of Southern manufacture. It included two blowing engines and ten boilers, thirty feet long and forty-six inches in diameter. In April 1882, the furnaces went into blast. After its first year of operations, the furnace had sold 24,000 tons of iron. At the 1883 Louisville Exposition, the company won a bronze medal for ‘best pig iron.’

During the 1880s, as pig iron production in Alabama grew from 68,995 to 706,629 gross tons, no fewer than nineteen blast furnaces would be built in Jefferson County alone. Per Dr. W. David Lewis, author of Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District, Sloss Furnaces was born at a time when the “doldrums of the postwar era had ended and the South was feeling a measure of confidence for the first time since the opening years of the Civil War.”

(Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark/Facebook)

Town planners, railroad magnates, and industrialists such as, Sloss received, as one Alabama newspaper stated, “a degree of adulation previously reserved for military heroes.” In November 1881, the Birmingham press promoted Sloss as a candidate for governor. “His excellent business qualifications, brilliant intellect, splendid character, and fine executive ability, all combined, make him the grandest man in Alabama today for our chief executive. He is the very personification of Christian manhood and integrity, possessing the qualifications of head and heart which we should emulate.” Inspired by such rhetoric, Alabama, not surprisingly, eagerly embraced what was being called the “gospel of industrialism.”

James W. Sloss retired in 1886 and sold the company to a group of financiers who guided it through a period of rapid expansion. The company reorganized in 1899 as Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron, although it was never to make steel. With the acquisition of additional furnaces and extensive mineral lands in northern Alabama, Sloss-Sheffield became the second largest merchant pig-iron company in the Birmingham district. Company assets included seven blast furnaces, 1500 beehive coke ovens, 120,000 acres of coal and ore land, five Jefferson County coal mines and two red ore mines, brown ore mines, and quarries in North Birmingham. By World War I, Sloss-Sheffield was among the largest producers of pig iron in the world.