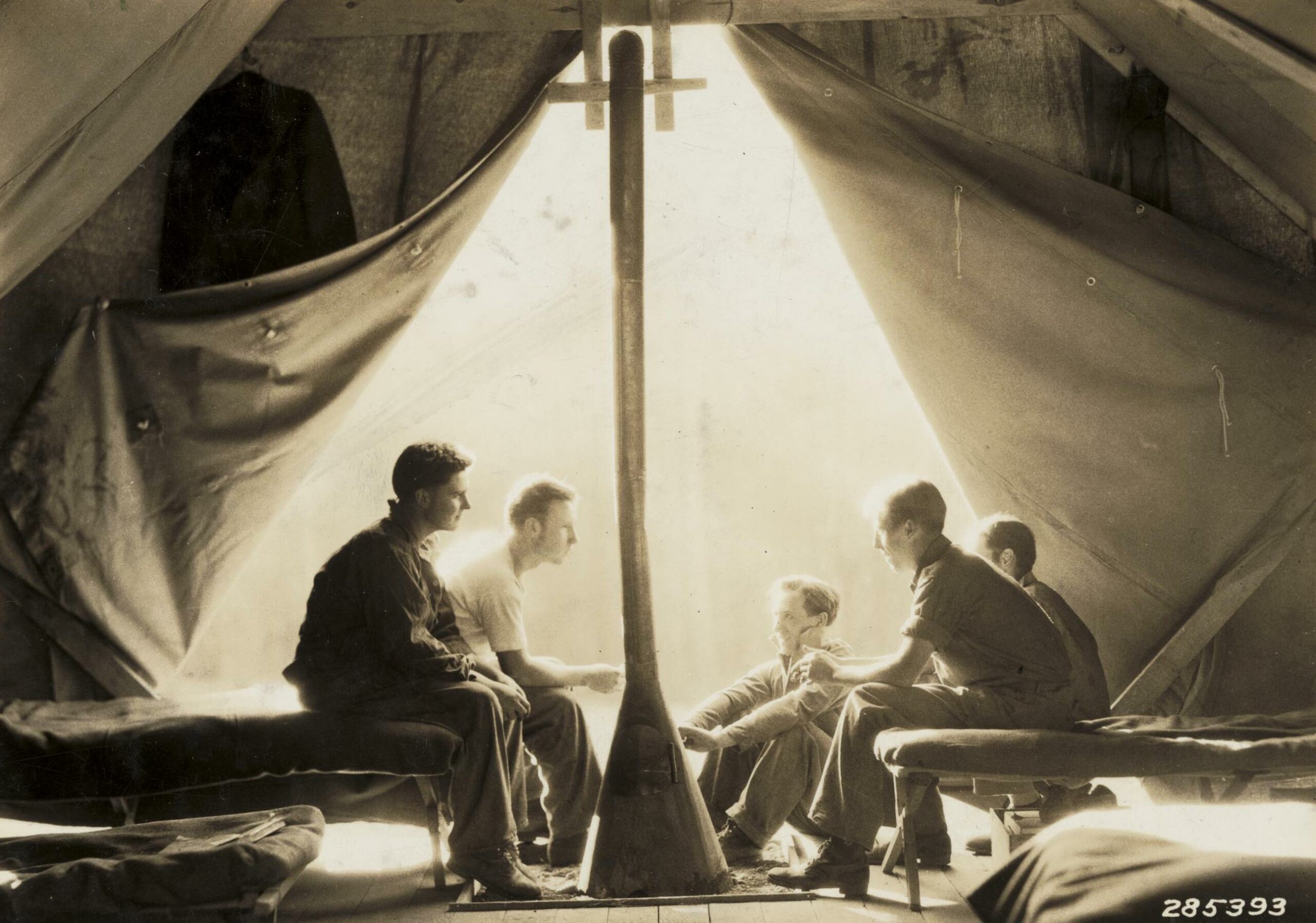

Ninety years ago, the Civilian Conservation Corps sprang to New Deal life. From 1933-1942, the CCC created a long-lasting impact on Alabama. Around 66,000 young men (White and Black, working in separate companies) built 1,800 miles of roads, nearly 500 bridges, improved hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland, and helped create 12 state parks, including some of the state’s most iconic park architecture. Think of Bunker Tower atop Cheaha Mountain, Jones Archeological Museum at Moundville, and the Open Pond Fire Tower in Conecuh National Forest.

(Alabama Humanities Alliance/Contributed)

Below, we asked several Alabamians to share about some of their favorite CCC spots. To learn about other CCC sites in the state, visit the Encyclopedia of Alabama and watch the AHA-funded documentary, Rural Revival: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Alabama.

- While growing up in Anniston, Alabama, my bedroom on the top of 10th Street Mountain Road looked out at Cheaha Mountain. At first, my imagination created its own story of the Mountain. What better place on earth to encounter God’s majesty than at Alabama’s oldest state park, its highest natural point, its most mesmerizing vista of the southern-most Appalachian Mountains? Alabama’s earliest inhabitants, the Muscogee Creeks, gave the mountain its name; in the Mvskoke language, Cheaha means “high” or “high place.”

–Wayne Flynt, Ph.D., historian, author, and Alabama Humanities Fellow (1991)

- The Triana Health Clinic, a stone-clad, Craftsman structure, was originally built in 1941 by the CCC as a game warden’s residence within the Wheeler Wildlife Refuge. But it most notably operated as a public health clinic for over four decades in the quiet river town of Triana. The clinic was instrumental in providing healthcare to rural, low-income Black families in north Alabama, thanks to the direction of two medical pioneers, Harold Fanning Drake, M.D., and Nurse Johnnie Loujean Dent.

–Betty Williams, president, Triana Historical Society

- In Spanish, Monte Sano means “mountain of health,” an apt description for Monte Sano State Park, in northeast Alabama. Here, there are 11 original CCC stone cabins with working fireplaces and screened-in porches, which were handcrafted in the 1930s. Cabins sit along a bluff line with a breathtaking view of the valleys surrounding Monte Sano Mountain. A CCC Museum and a Memorial Garden sit on the park’s summit, dedicated to the young boys who created the structures.

–Tommy Vincent Wier, filmmaker, ‘Rural Revival: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Alabama’

- Beneath towering oaks, the sandstone gateway into DeSoto State Park is a standing testament of the hard work of the CCC boys. Visitors can touch the chisel marks in each giant stone, walk to an unfinished mystical stone bridge, or hike to the park’s sandstone quarry where the CCC sourced stone for these beautiful “parkitecture” structures.

–Renee S. Raney, chief of interpretation and education, Alabama State Parks

- The former Fort McClellan in Anniston once served as a multi-state headquarters and supply district for the CCC. Closed in 1999, McClellan is now home to a vibrant civilian community that retains much of its rich history, including the Fort’s historic cemeteries, Monteith Amphitheater, and former Officers’ Club — a deteriorating relic in need of repair, whose lounge is filled with massive, breathtaking murals painted by two German prisoners of war held there during World War II.

–W. Pete Conroy, conservationist, director of JSU’s Environmental Policy and Information Center

(Alabama Humanities Alliance/Contributed)

Country cemeteries have as many stories to tell as souls at rest. Below, Alabama scholars share a mere sampling. To learn more about historic cemeteries statewide, connect with the Alabama Cemetery Preservation Alliance.

Brown Cemetery | Sumter County

In 1848, the John E. Brown family built The Cedars, a large home on former Choctaw land in Sumter County. The people they enslaved, and their descendants, occupy nearby Brown Cemetery, noteworthy for its handmade headstones. Fashioned in a wooden mold from cement, they are hand-lettered or stamped and many bear at the top a stamped flower, cross, or other design. These folk markers can be found across Sumter and surrounding counties, their similarity suggesting a limited number of makers.

–Ashley A. Dumas, Ph.D., associate professor of anthropology, University of West Alabama

Camden Cemetery | Wilcox County

Camden Cemetery is the final resting place of the victims of the Orline St. John steamboat tragedy. The sidewheeler caught fire on March 5, 1850, while traveling north on the Alabama River. Over 40 people, mostly women and children, perished. The ship’s captain was the Mobilian Tim Meaher; presumably the same Tim Meaher who, a decade later, would infamously and illegally traffic the last enslaved Africans into the U.S. aboard the Clotilda.

–Mollie Smith Waters, AHA Road Scholar and professor at Lurleen B. Wallace Community College

Claiborne Cemetery | Monroe County

In the woods by a cow pasture in what used to be Claiborne is a surprising find — a 19th-century Jewish cemetery. What used to be a bustling river town in the 1850s had a small Jewish community, working as peddlers and rural merchants. Though newcomers, many fought for the Confederacy. Union looting during the war, yellow fever, and a railroad snub led to the town’s demise in the early 1870s, and most remaining Jews headed to Mobile or Selma. Teens from a Jewish summer camp in Mississippi helped restore the cemetery in 2000.

–Larry Brook, editor, Southern Jewish Life

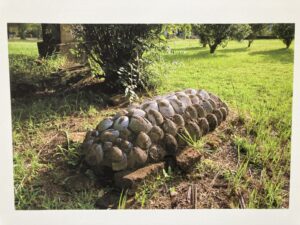

Key Underwood Coon Dog Memorial Graveyard | Colbert County

Alabama’s famed “Coon Dog Cemetery” was founded, unwittingly, in 1937, when Key Underwood buried his dog and longtime hunting companion Troop here. The pine bluff, known as Sugar Creek, had been the duo’s favorite hunting ground. Several years later, Underwood’s brother buried one of his own coon dogs at the same spot. A tradition took hold. Today, the cemetery is the final resting place for more than 300 coonhounds, and nearly 7,000 people visit each year.

–Karren Pell, contributing author, Encyclopedia of Alabama

Pioneer Cemetery | Butler County

Greenville’s oldest cemetery showcases two types of classic Southern cemetery architecture. One is evident on the 1864 grave of a 21-year-old Anna Catherine Reid, covered in cockleshells, one of the most popular Southern grave-decorating traditions of centuries past. The other example is Elizabeth Bragg’s 1870 grave, graced with an elaborate metal cover crafted by local inventor Joseph R. Abrams. His Greenville grave covers would become popular the South over in the late 1800s.

–Annabel N. Markle, Pioneer Cemetery Preservation Association

Note: This story is reprinted from the 2023 issue of Mosaic magazine, published by the Alabama Humanities Alliance. Read the issue in full at alabamahumanities.org/mosaic.