With more than 40 properties and multiple districts on the National Register of Historic Places, Tuscaloosa houses a great deal of history in the most literal of senses. However, the struggle to keep these structures standing can be significant, and not all buildings survive.

“Tuscaloosa’s lost so much,” Nika McCool, the current owner of the Drish House, told me. She urged me to look up photos of the city from the 1950s and ’60s. She brought up the Searcy House, which became a parking lot in 2016—right around the time when she and her husband were finishing renovations on the Drish House. “It’s hard. Those older places, they’re really irreplaceable,” she said. “They encapsulate the soul of your town in a way that nothing else does.”

(Drish House/Contributed)

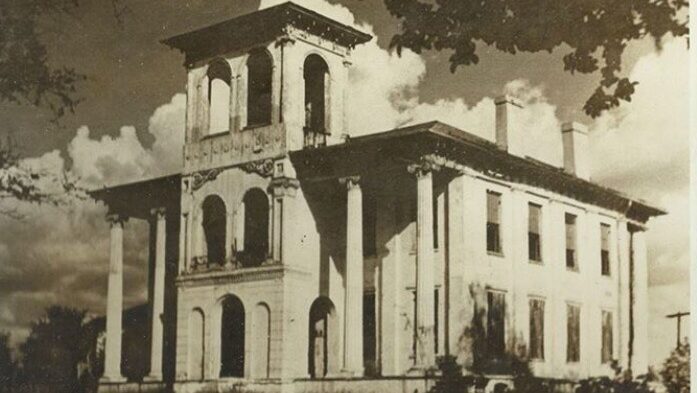

To McCool, the Drish House is more than just an event venue; it’s history. Built by enslaved craftsmen in 1834, the home’s original owner, she said, “perfectly encapsulates the rise and fall of the cotton kingdom…you think of the Antebellum South as lasting a long time, but it really was one person’s lifetime.”

Dr. John Drish moved to Alabama from Virginia to buy 500 acres of seized Choctaw land, which was being auctioned off by the federal government. He built his home at the very edge of the budding town of Tuscaloosa. From there, he ran his plantation, served as a state legislator, owned part of a railroad, and worked as a local doctor. Like many men of his era, he was also his own architect.

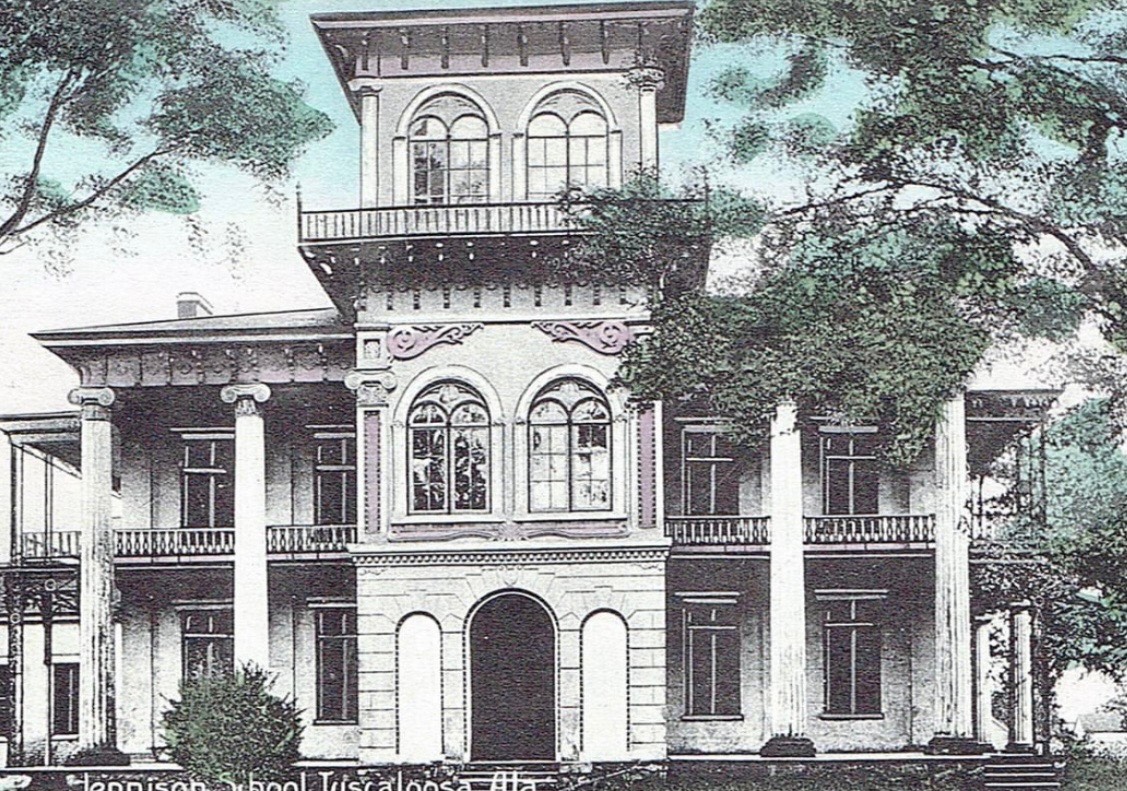

Of his efforts, McCool remarked, “Our house is this weird mix of architectural styles.” Dr. Drish not only built the home, but conducted 2 major renovations over the course of his lifetime. “It was originally a Federal-style structure, similar to the houses he had known in Virginia. And then he did this sort of Greek Revival thing… for that, he had to put a different roof on the house, so there are 2 roofs on the house. We ran into that while renovating, and that was a problem. And then Italian architecture became the vogue, so he added the kind of weird tower. You know, the tower’s my favorite architectural thing—I think it makes no sense at all. It’s a little disproportionate. It cracks me up every day.”

At the same time, preserving a house like the Drish House requires reckoning honestly with the conditions under which it was built. While Dr. Drish’s life is well documented through letters and journals, the stories of the enslaved craftsmen who physically constructed the house are largely lost to time. Preservation, McCool believes, isn’t about glorifying the past, but about holding space for its full complexity. The building stands as both an architectural landmark and a reminder of the labor, displacement, and inequities that shaped Alabama’s early history—realities that cannot be separated from the beauty or significance of the structure itself.

(Drish House/Contributed)

The only enslaved craftsman whose name is known is William Drish, an enslaved master plasterer. Some of his work survives in the Drish House tower, as well as on the University of Alabama’s campus and at Bryce Hospital, another Tuscaloosa landmark. McCool mentioned that sometimes, when she’s out and about in town, she thinks she spots traces of his handiwork elsewhere—small, quiet connections between buildings that have outlived the people who made them.

After Dr. Drish and his wife died, the house changed hands several times as a private residence. In 1910, it took on a new role as one of Alabama’s earliest public schools. The school outgrew the house in the 1930s, but the city retained ownership, eventually leasing it to an auto parts store. After the Depression, the city sold the building to Southside Baptist Church, which occupied it until the 1990s.

By that point, the Drish House was dangerously close to being condemned. The Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society stepped in to prevent demolition, but lacked the funding to do more than stabilize the structure. In 2012, the society finally found a family willing to take on the enormity of the restoration: the McCools.

“It was dark and weird and stinky—smelled like 1 billion barn cats in there,” McCool recalled. Her banker was nervous about the purchase, but the McCools were resolute. “It needs to be saved,” she remembered thinking, “and no one else is stepping up to the plate.”

At the time, the house had no electrical system, no plumbing, and no ceilings—the latter removed due to severe infestation. Parts of the second floor were so unstable that you couldn’t trust your weight. Without HVAC, the house was pitch-black and, in the summer, “hot as blazes.”

(Drish House/Contributed)

The renovation process took 2 years. “Most of it was library work,” McCool said. Challenges included tracking down historical brick mortar recipes so new bricks wouldn’t crush the old ones, commissioning custom-sized windows, and navigating countless other details. While the goal was always to preserve as much original material as possible, some losses were unavoidable. McCool still mourns the wraparound porch that once encircled the tower. “If I could do anything, I’d have the upstairs porches back,” she said. “I don’t know if you could replace that workmanship even if you had the money.”

Over the years, the Drish House has also earned a reputation for being haunted—a layer of folklore that now exists alongside its documented history. Visitors and locals alike have shared stories of unexplained sounds, shifting temperatures, and the feeling of a lingering presence, legend that has woven the house even deeper into Tuscaloosa’s Southern Gothic imagination.

Today, the McCools have transformed the Drish House from a barely standing structure into a thriving event venue. The goal of the restoration wasn’t simply to preserve old Tuscaloosa, but to create space for the city as it exists now. “We try really hard to remain poised between preserving the past and looking forward to what’s to come,” McCool said. “I want that house to be a vibrant hub where people can gather for educational programming and community-based events.” Weddings, she added, are among the most common gatherings hosted there.

“I feel a lot of satisfaction,” McCool reflected. “The Drish House is now 180 years old—and it could go for another 180.”